What Good is MMP Anyway?

November 11, 2009

This is the next in several posts on MMP and the debate around whether it should be retained or done away with in the referenda to take place over the next few years. Here I ask: What good is MMP anyway?

The traditional wisdom on proportional systems versus majoritarian systems (or MMP vs. FPP) is that proportional sytems are ‘nicer’ and more inclusive, whereas majoritarian systems are more effective. The logic behind this is pretty straightforward: The more parties in government, the more people get to have a say; with only one party in government decisions get made in a quick, decisive way.

But does this logic hold? Actually, in 1999 it was blown out of the water. Political scientist Arend Lijphard categorized 36 countries as consensual or majoritarian, but he also asked the ‘so what?’ question, and he found that on the whole the traditional wisdom was unfounded: there is no trade-off between quality and effectiveness of democratic government.

1. Economic development is at least as good under proportional (MMP) systems as under FPP. Successful macroeconomic management needs a steady hand as much as a strong one, and MMP systems are in fact better at managing inflation than FPP systems (though this is probably because they are associated with independent central banks).

2. Consensual systems like MMP are associated with less political violence like riots.

3. Consensual systems provide for better democracy: Higher voter turnouts, higher representation of minorities and women, more equal distribution of political power and less corruption.

4. Consensual systems are ‘nicer’: they have less people in prison and are less likely to use the death penalty, they have better social welfare systems, they are better at protecting the environment and provide more foreign aid.

Obviously you will have to read the book and look at the statistical analyses, but taken at face value these conclusions rob opponents of MMP of one of their main arguments: We can have our cake and eat it too – there is no trade-off between inclusiveness and quality of government and effectiveness or economic growth.

Who Will Stop MMP Reform?

November 5, 2009

To continue the analysis I started in my previous post on the apparent unpopularity of MMP in NZ and its possible demise I ask: Who will try and stop a move back to First-Past-the-Post electoral procedures? Let’s take a purely utilitarian approach to this question.

In Parliament, the opposition must surely be opposed to a government which seems to seek to change the electoral ‘rules of the game’ to its advantage. And I believe the Labour party will oppose a move away from MMP, ostensibly for the reason I mentioned previously: Labour has traditionally had more allies with which to form coalitions under MMP, and can thus consider the current system to be to its advantage.

Because the matter will be decided by a public referendum, one could assume that Labour supporters and supporters of all small parties would vote against a move away from MMP and as a bloc form a majority. National did not win a clear majority in the last election after all.

However as the last post showed, not only National supporters are advocating a change back to First-Past-The-Post. Why? And without a Labour-Small Party bloc who will support MMP?

I suggest that National’s success in wooing the Maori Party and United Future has changed some Labour supporters’ view of the ‘rules of the game’ of MMP in that they no longer see themselves as a priviliged player under MMP compared to National. If National can also form coalitions with three or more smaller parties, what are the benefits to Labour from MMP (over and above those for National, it goes without saying)?

There are none. Labour supporters are therefore put in a position the same as National supporters were up to now: they have no reason to support proportional representation when they could govern alone under First-Past-the-Post (except ideational reasons which I may look at later). By this reasoning, if voters vote according to their parties’ interests at the referenda only small party supporters will support PR and MMP should be shown the door.

How to explain politicians’ continued support of MMP? They are hedging their bets, maintaining their popularity in the eyes of smaller parties, who they will have to work with until 2014 at least, and perhaps beyond if the referenda fail.

New Poll Shows NZers Unhappy with MMP

November 1, 2009

There is a very interesting poll on the NZ Herald website today which shows most New Zealanders would like to change their electoral system away from MMP. 49% said they would vote against MMP at a referendum, 36% said they would vote for it and 15% said they didn’t know which way they would go. There is to be a referendum on whether to keep MMP at the next general election.

To compare these figures to the results of the election a year or so ago: Then only 14% of voters voted for a small party – that is not for National or Labour (but excluding those who did not make it into Parliament). So MMP obviously has support outside its core demographic of voters who do not subscribe to the two main parties.

However, a larger proportion of respondents are against MMP than voted for National at the last election: 49% versus 45%. I find this a little surprising, as my first instinct on MMP reform was that it was just a case of the victors being able to change the rules of the game to ensure their continued electoral success: National has always had a lesser number of willing coalition partners than Labour and thus would prefer a return to FPP. (Yes, I maintained this belief despite John Key’s sincere utterings that most NZers want to stick with MMP – which have been proved to be wrong).

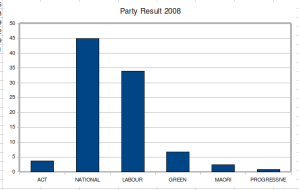

But this result seems to indicate something a little deeper than that: It is not just National, but also Labour, supporters wanting to get rid of proportional representation. The flip-side of the 14% of people voting for smaller parties are the 79% of people voting for either Labour or National, as shown below.

As this graph makes visually clear, if supporters of the two main parties decide that they no longer want proportional representation, and would rather govern alone without coalition partners, they will always be able to push this through.

This is, of course, a simple case of majority rules and exactly what MMP was brought in to prevent. Should the change to MMP therefore be regarded as an anomaly; a short period where the majority were so disillusioned with politics that they were prepared to allow minorities a more significant say, which has now passed?

Of course we will have to see what the results of the actual referenda are, but this initial poll result would suggest that supporters of both main parties are a little more cold-blooded in their attitudes towards minorities than one might have expected.

Coalitions in Germany and NZ

October 19, 2009

Three weeks after the Bundestag election in Germany and the discussions between CDU, CSU and FDP continue. It is still not clear what the exact policy directions of the new coalition government will be, or who will occupy which ministerial/government posts.

I see an interesting difference in the coalition bargaining between the parties and what has gone on in NZ after MMP elections since 1996.

The German parties are driving hard bargains. Both the CSU and FDP are sticking to their guns and placing demands on Merkel’s CDU that they make concessions so the smaller parties honour their pre-election commitments. There have been several examples of this as the discussions have gone on, for the FDP most notably in measures protecting personal privacy.

But as predicted, the big one sticking point is tax cuts: both smaller parties want them, the CDU knows they can’t really afford them. Merkel doesn’t want to be seen as fiscally irresponsible and run large deficits just to finance tax cuts (and the CSU will not allow this anyway). The result is a sort of Mexican stand-off. This has been going on for weeks. It has finally been decided that there will be tax cuts, the question is how big they will be.

The important point here compared to NZ is that the coalition bargaining is very detailed, and very contested. I am not an expert on NZ’s coalition agreements, but NZ moved away from both these aspects after the first experience with coalition government in 1996.

Then, Winston Peters and NZ First undertook to draw up a coalition agreement which set out most important policy directions in writing. Peters drove such a hard bargain that he was seen to be holding the country to ransom, and the discussions took so long that the country was without an effective government for two months. NZ First ended up going with National, which was the opposite of what they had alluded to pre-election. The coalition didn’t last very long, and neither did NZ First’s (or MMP’s) popularity.

Since this negative experience with detailed, drawn-out coalition bargains NZ has moved to a more flexible approach based on agreements on confidence and supply (settling other issues on a more ad-hoc basis), which would seem to be more in keeping with the country’s Westminster/common law tradition. Helen Clark’s Labour did this with the Greens in 1999/2002 and with NZ First/United Future in 2005. John Key has a similar confidence and supply agreement with ACT, United Future & Maori Party.

The Germans, however, seem happy to persist with longer, more contested coalition bargaining phases in which major policy issues are hashed out in detail after the election. This is more in line with the German tradition of constitutional consensual government, and the German civil law.

CDU/CSU and FDP win 2009 Bundestag Election

September 27, 2009

The first unofficial results for the election are in:

CDU/CSU: 33.5%

SPD: 23.3%

FDP: 14.6%

Left Party 12.9%

Greens: 10.2%

This situation should be enough to give the conservative CDU/CSU and the liberal FDP enough seats to form a ‘bourgeois government’.

The results for the two big parties are their worst ever; the FDP has its best result in a decade. This election could also set records for another reason: It seems approximately 5% less people cast their votes than at the last election (which was the lowest rate ever).

Neither the SPD or CDU/CSU is impressed with its results; both are blaming the Grand Coalition for their losing an independent profile and driving voters away or to smaller parties. However the Union has achieved its main goal: to govern without the SPD. Angela Merkel’s position is now very strong and this victory will cement her leadership credentials in the conservative Union against the many ambitious potential challengers in her party.

An FDP/Union coalition should really bring about the pro-market reforms that Merkel campaigned for in 2005 but was not able to enact in the Grand Coalition. However the shadow which hung over this year’s election campaign, huge budget deficits for years to come due to bank bailouts in the financial crisis, will severely impede Merkel’s capacity to enact reform. Tax cuts in particular, a favorite goal of the FDP, do not look likely and were laughed off by SPD finance minister Peer Steinbrueck during the campaign as simply impossible.

The SPD is quite open about its result being a disaster. The question is where the party goes from here which, quite frankly, no one can say at the moment. There will be a lot of long faces in the SPD, where many had hoped that another Grand Coalition would allow the party to distribute a decent number of Ministerial and State Secretary positions; a simple Bundestag salary and position in the Opposition pale in comparison.

MMP: What about Politics?

September 25, 2009

Due to the upcoming referendum on the MMP electoral system in New Zealand, there have been a raft of blog postings on the performance of the present system, what people would prefer in a new electoral system, what the effect of the 5% threshold is, and different types of electoral system.

These all make for interesting reading, if you are interested in arcane electoral mechanics, mundane spreadsheet calculations and the functioning of democracy in obscure countries (like NZ).

However they all miss one aspect of the debate around MMP, and that is Politics, or ‘Who gets what, when and how’.

They seem to assume that NZ politics will be solely defined by its electoral system and miss other things such as public opinion, political parties, interest groups, political culture, the list goes on.

It is therefore worthwhile asking: Would having a different electoral system change NZ politics? The answer is, not very much. The changes would be on the fringes: with perhaps slightly higher representation for smaller parties in Parliament, and perhaps the creation and representation of a new party or two.

Due to the inate tendency of party policy to tend to the middle, it can be safely assumed that the majority of the votes cast will be gathered by two large parties who battle it out for the chance to form a government.

Sound familiar? Yep, it sounds like democracy pretty much all over the world. That’s the beauty of not examining an electoral system in isolation but in its context, Politics.

Mrs. Merkel, Who Will It Be?

September 23, 2009

So five days out from the election to the German Bundestag it is now fairly clear that there are only two possible results:

1) Another Grand Coalition

2) A CDU/CSU – FDP coalition.

Why? Firstly because the SPD and Greens do not have much of a chance of getting enough votes to form a coalition. This has been clear since before the start of the election campaign and has not changed: As of today’s poll, the SPD is on about 24% and the Greens 11%. Together, 35%. Doesn’t cut it.

Also, as before the SPD rejects a coalition on the Federal (Bundestag) level with the Left Party. Not that that would be possible going by current polling because the Left gets only 11.5%. Add that to the SPD and Greens and you still don’t get a majority.

Finally and most interestingly, on Sunday the FDP leader Guido Westerwelle came out and finally categorically rejected a so-called ‘Traffic Light Coalition’ of Greens, SPD and FDP.

So the question (which has only be slightly narrowed since July) is: Will Chancellor Merkel be able to form a ‘bourgeois coalition’ with her preferred partner the FDP, or will it be business as usual in a Grand Coalition come Sunday? The CDU/CSU has 35% and FDP 13.5% on current polling.

The word is that the overhang mandates – direct mandates won in electorates exceeding the overall proportion won by the party in the country – will tip the balance in favour of the CDU/CSU and FDP. The SPD are already complaining that this is a misrepresentation through the electoral system, which some are seeing as a concession of defeat.

A reinstating of the Grand Coalition would certainly be a dull ending to a dull election campaign, where neither of the larger parties has confronted the other on any substantial issues of policy or personality. So maybe it would fit.

Duel or Duet?

September 15, 2009

This week we saw the much-anticipated TV debate between CDU/CSU leader and Chancellor Angela Merkel and her challenger Frank Walter Steinmeier from the SPD. It was hoped that this would bring out the fighting spirit in both of them, or at least one of them. However it was, alas, a flop.

Concerned more with patting themselves on the back for their fine work during their grand coalition of the past four years than attacking each others’ policies, the two candidates avoided direct criticism of each other. Even during the debate, the frustrated TV presenters were calling it ‘more of a duet than a duel’.

Both major parties are, predictably, calling the debate a victory for themselves; voters see it as a draw. If anything, Steinmeier surprised viewers – however one can assume their expectations were low. He was rated in polls after the debate as ‘more convincing’.

Apparently, the Greens/FDP/Left Party TV debate was much more entertaining, but I haven’t looked at it yet.

Always good for a laugh, the tabloid paper Bild led an article on the duel with a hilarious pun playing on an Obama campaign slogan: ‘Yes We Gähn’ (Yes We Yawn).

Public enthusiasm for the election so far has been low, and German comedian Harpe Kerkeling has made good mileage out of his satire based on a fictional Chancellor candidate, Horst Schlemmer who is ‘liberal, conservative, and left’ (His election slogan is another interpretation of Obama: Yes Weekend!).

Key’s ‘Labour Lite’ and Why Parties Move to the Middle

September 9, 2009

Remember back to before NZ’s November General Election and the scrutiny of National’s leader and future Prime Minister John Key? He was labeled as ‘Labour-lite’ and centrist; his party was careful not to wage war on some of Helen Clark’s more popular policies; the differences between the two main parties were small, negligible even.

And for those who follow US politics – you must have been struck by the partisan divide in both society and politics between the Democrats and Republicans. It is, in the words of a columnist, ‘The 50/50 Nation‘. Heck, the two camps even have their own separate news channels!

Over in Germany, people ask themselves: What is the SPD doing in opposition? (oops, sorry, the election isn’t for 2 weeks. I meant, Grand Coalition.) They could form a government with the Greens and the Left Party tomorrow!

Discussion of all these issues, and some others which I have speculated upon here previously, can be informed by a powerful, but simple, political science model (originating in economics) called the Median Voter Theorem.

Briefly, the theorem is a model of majority decision making which states that the median voter’s preferred policy will beat any alternative in a vote; in a stronger form it also says that the median voter will almost always get his/her most preferred policy. The rationale behind it is too much for this blog and is explained briefly and clearly here, but the consequences are far-reaching.

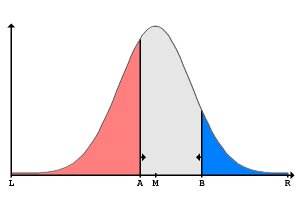

If we apply the model to the Left-Right spectrum above, we can come to the following conclusions:

If we apply the model to the Left-Right spectrum above, we can come to the following conclusions:

1) if voters cast their vote for the candidate closest to their ideal policy, then the candidate who stands nearest to the median voter will win. In this case, this would be candidate A, who is closest to point M.

2) if the candidates are free to choose their policies, they will choose positions which will place them closest to the median voter’s at M; so candidates A and B will move in the directions of the arrows towards the middle of the graph and the median voter’s preferences will be fulfilled.

The theory puts the median voter in the lucky position of always getting what they want, but it also has other consequences – many more than will be expanded on here, but to go back to the examples above:

Key vs. Clark in NZ: parties will choose policies which are moderate and middle of the road; no wonder that they look so similar.

Democrats vs. Republicans in the US: if parties continue to act as above for many years they could create blocs, each accounting for approximately half of the population (see the column from Mickey Kraus).

The SPD and the Left Party in Germany: parties will be very careful not to take extreme positions which could alienate voters closer to the median.

So there you have it. A brief but hopefully not-too-incomplete rundown of the Median Voter Theorem in five minutes. A simple, powerful analytical tool for analyzing party politics.

Wahl Watching

September 2, 2009

Excuse my awful pun: The German word for election is ‘Wahl’. I thought I might post on the federal election campaign over there seeing as I have neglected it for a couple of weeks.

As for how the parties stand in the polls: The smaller parties (FDP, Green and Left) are all looking pretty much the same – between fourteen and ten percent each. The SPD is still looking pretty dismal, but has risen from its all-time low of 20 to 22%. The CDU/CSU is down from a high of 38% to 36%. So not much movement there really.

This is how the Bundestag would look according to current polling (from Spiegel Online):

However, one development has added a certain element of uncertainty: The poor results of the CDU/CSU in the state elections in Thüringen and Saarland this weekend, where they will probably lose the state premierships.

Of course this has given the SPD some encouragement, but mostly it has just kicked off a wave of speculation on coalition possibilities at the federal level: Will the CDU/CSU prefer another Grand Coalition with the SPD if it cannot form a government with its preferred partner the FDP? Will the SPD be tempted to enter into a (up to now taboo) coalition with the Left Party in the same situation? The list could go on.

There has also been some criticism of how Merkel is campaigning: Not enough criticism of the SPD and Left and not enough real policy debate, say some. Her tactic seems to be to stay the self-confident Stateswoman and win the race to the middle without alienating support from the left.

And what are the big issues of the campaign so far? Well, the two which stick out are Unemployment and Tax Cuts, from the SPD and CDU/CSU respectively.

SPD promises of full employment within ten years have been scoffed at (probably rightly) by the CDU as unachievable – we have seen such promises go unfulfilled by Schröder’s government, they say. The promises of tax cuts from the CDU/CSU have been slammed as unrealistic and unachievable by the man who should know best – current SPD Finance Minister Peer Steinbrück. So it seems like a bit of a stalemate there.

Despite these side-shows the real question is by how much the CDU/CSU will win and whether it will be able to form a government with the FDP. With its poll results very low, and lacking a charismatic Chancellor candidate or mobilising campaign issues, the SPD is still looking very much the underdog.